Know Pain, Know Gain: What Patients Want to Know About Pain

By: Nataliya Zlotnikov HBSc, MSc ∙ Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

By: Nataliya Zlotnikov HBSc, MSc ∙ Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

The Leaning Tower of Pisa: Why Does it Lean?

On August 9, 1173, construction began on the Tower of Pisa (they didn't mean for it to lean), but when the tower was just over 3 stories tall, construction stopped for unknown reasons.

Perhaps it was due to economic or political strife, or maybe the engineers noticed that the tower had begun to sink down on one side because of the unstable foundation it was built on (History, 2022).

Whatever the reason, after a 95-year pause for the occasional war, debt, and engineers working on solutions to correct the lean, the construction on the tower continued (Leaning Tower of Pisa, 2022).

Finally, in 1370, about 200 years after the first marble stone was laid, the tower was officially completed. But it would continue requiring considerable efforts and formidable financing to prevent it from tilting even further or toppling over (History, 2022).

The Leaning Tower of Pain Education

The Leaning Tower of Pisa can teach us a lot about how we perceive healthcare education.

There are so many patients living with persistent pain who have not had their foundational questions about their pain answered.

Education IS the foundation; it’s the thing that helps people build and recover.

If you can understand the situation, you will be more confident in getting back to doing what you love.

Learn more with Mike

What are the Foundational Questions?

The foundational questions that patients have not had answered include ones such as:

- Why do I still have this pain?

- What do I do about it?

- What's wrong with me?

- How long will it take me to get better?

- What do I need to do for this to get better?

- Why have I had this pain for so long?

What Else Do Patients Want to Learn About Pain?

Building on the foundational questions mentioned earlier, a recent study by Leake et al. (2021 aimed to explore what patients prioritize in their understanding of pain.

The study identified specific pain concepts valued by individuals with persistent pain who experienced improvements following a pain science education intervention.

The authors found 3 themes, representing overarching concepts identified by the study participants as important for their recovery:

- Pain does not mean my body is damaged

- Thoughts, emotions, and experiences affect pain

- I can retrain my overprotective pain system

![]()

The majority of pain science education concepts have developed in a top-down manner.

Currently, we do not know which concepts in pain education interventions are most important to those who live with persistent pain, or that they attribute as key to their improvement.

-Leake et al., 2001

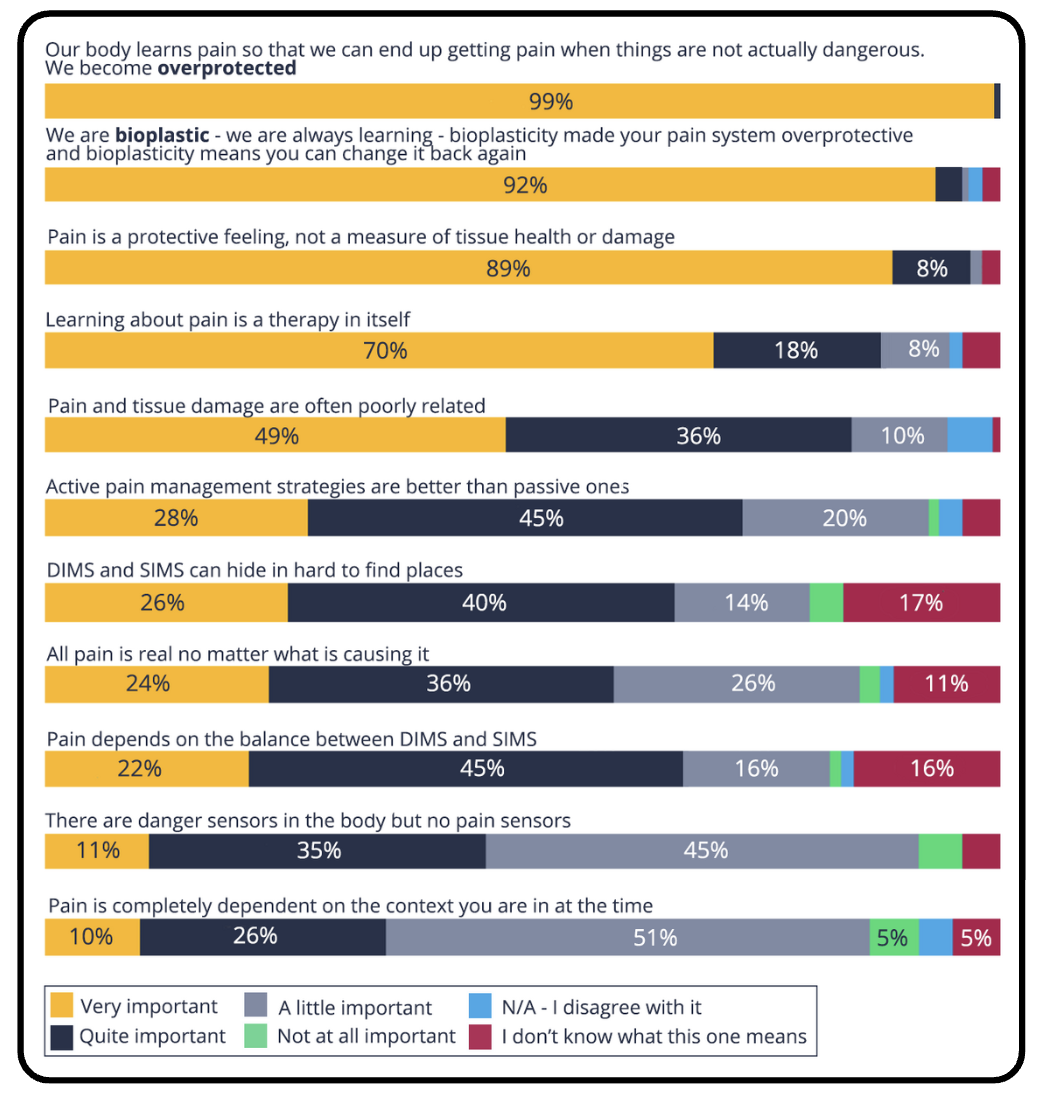

Perceived Importance of Pain Education Concepts

This figure, adapted from the study, illustrates the distribution of ratings for the perceived importance of pain education concepts among individuals with persistent pain who have benefited from a pain science education intervention.

Note that shaded values represent categories with less than 5% of responses.

Education allowed the patients in this study to answer many of the foundational questions and alleviated fears regarding their current and future health.

Tame the Beast, Rethink Persistent Pain

The current best evidence supports the therapeutic effect of pain science education, with studies showing pain education provides strong evidence for reducing pain, disability, pain catastrophization, and limited movement (Diener et al., 2016).

Here is a simple and informative pain education video you can share with your patients from Lorimer Moseley, also available on Embodia.

This video is a great pain education tool for patients, and it's just so darn cute!

We have a great collection of pain education videos, images, and texts for you to share with your clients.

You can find them by signing into your Embodia Tier 2 or Tier 3 account and clicking on HEP, Education.

Sign into my Embodia account

Pain Science Education History Lesson

History is not only about the study of the past, but it is also a lesson for the future.

Why look at the history of pain science?

It is important to review this history to remember that what we once knew as truths can change with research over time.

We look at the past, present, and future of healthcare to make sure we are using proven methods and not harming our patients.

"As clinicians, we must be sure that the theories of treatment that we use are correct" PainScienceCenter, n.d.).

Back to Italy

With that out of the way, let's continue with our European journey through time!

As our leaning Tower—in all its unstable glory—was nearing completion circa 1370, a little east of Pisa, over in Florence, the Renaissance was just firing up (History, 2022).

During this period, thinkers shifted from the belief that pain was a religious and spiritual experience to a phenomenon that could be studied under the microscope (Louw et al., 2016).

Emerging from this was the Cartesian model of pain, commonly referred to as the biomedical model of pain, first proposed by French philosopher, mathematician and scientist Descartes in the 16th century (Physiopedia, 2022).

The biomedical model states that pain and injury are interrelated, and so an increase in pain means further tissue damage and vice-versa.

But sitting at over 450 years old, many now believe this model to be inaccurate and significantly outdated (Physiopedia, 2022), yet still commonly used in physical therapy practice (Louw et al., 2016).

Controlling Biopsychosocial Matrix Gates

A few hundred years after the development of Descartes' model, our increased neurobiological understanding of pain led to the creation of the Gate Control Theory (1965, Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall).

This model served humankind for more than half a century as a key element in the understanding and treatment of pain (Louw et al., 2016).

But understanding that the Gate Control Theory was not complete, in 2001, Melzack created the pain neuromatrix, an attempt to include all concepts of pain found in current research.

Currently, the neuromatrix is the most scientific and up-to-date explanation of pain (PainScienceCenter, n.d.).

Melzack's neuromatrix served to support Dr. George Engel's biopsychosocial approach (introduced in the 1970s).

Too Much Pain Science Education?

Now, many of us understand that the biomedical model often falls short in explaining some of the complex issues of pain, such as central sensitization, peripheral sensitization, inhibition, facilitation and neuroplasticity.

And we know that biomedical models may even induce fear and anxiety, which may further fuel fear avoidance and pain catastrophization (Louw et al., 2016).

Because of the complexity of pain, we now increasingly use pain science education in our practices. And there is strong evidence in support of its efficacy (Diener et al., 2016).

So we now talk to our patients about pain.

But is talking all we're doing now?

![]()

While pain education is an extremely important component of our treatments,

education is most effective when combined with other interventions,

such as exercise, rather than when delivered in isolation.

-Leake et al., 2001.

With the increased focus on pain education as treatment, we may have shifted our focus too much on education, leaving behind some very important aspects of pain education, such as information from the interview and physical examination (Diener et al., 2016).

More on Pain

To learn more about pain science education, take a look at our blog, How Pain Education Can Be a Game Changer in Your Patient's Lives.

You can also check out our extensive collection of pain science online healthcare courses on Embodia here.

---

Date written: 22 March 2022

Last update: 16 December 2025

MCSP, SRP, MSC, PG CERT

Mike is a physiotherapist, researcher and university lecturer with over twenty years of experience in helping people overcome pain.

He has an MSc in Education and Physiotherapy and is planning a PhD focusing on how people in pain make sense of their experience. His published work has received international praise from the leading names in neuroscience. Mike teaches across a variety of clinical settings including elite sports, and is an advisor on pain management to the International Olympic Committee.

Mike is a dedicated practice-based educator committed to providing evidence-based education to a wide variety of health professionals. His Know Pain workshops have provided clinicians around the world with practical pain education skills.